Castaway

Part 1: Harper’s East Hampton | August 10 – September 28, 2024

Part 2: GANA ART Seoul, Korea | August 22 – September 22, 2024

Across his rigorous practice, painter Ho Jae Kim examines questions of liminality: the artist renders scenes of existential transition and disorientation, transcribing the wayward architectures of purgatory and other entrapped states. In Castaway, Kim continues to investigate the aesthetics and affects that color this psychic in between. He considers the film Cast Away (2000) as a cultural reference from which to address such interior reckoning. In the blockbuster film, Tom Hanks plays a man deserted on an island; with few tools and resources, he must learn how to endure the trauma of solitude. He personifies a volleyboy to cope with his loneliness, naming it Wilson. As Kim sees it, Wilson does not only function as a material object. Like an artwork, Wilson is the product of internal and external rumination––he embodies the protagonist’s psyche.

For Kim, the career of an artist fosters the kind of psychic alienation invoked by an uninhabited island. To produce work, an artist must engage in persistent self-reflection: they must undergo a vulnerable process of questioning their ideas, realizing them, and then ushering them into public viewership. The artist’s studio can thus be seen as a site of unprecedented hardship, but also nourishment—a place that challenges brave souls to uncover difficult truths. Kim encapsulates this schism in the work Studio Island. Here, a nude figure sits beneath the shade of a palm tree, painting hatch marks on a large canvas indexing time. The painting, like the figure, appears obscured, enshrouded by the darkness that likely awaits in a nearby jungle. But beyond the tree, light emerges: speckled beige brushstrokes color a brilliant sky and a sandy beach, like a silver lining of clarity after troubling introspection.

This meditative scene, like many of the featured works, appears weathered by its layers. Kim’s intricate process involves sketching, digital rendering, chemical transferring, and adding thick swaths of ink and pigment. The resultant works incorporate dense impasto, harboring the essence of many marks and concepts built into the fabric of each visual plane. This intricate process takes center stage in the textural work, Mythical Island. Here, a figure is engulfed by unforgiving terrain: compact coats of stirring gold, pink, and navy shade the forlorn intersection where the ocean meets the sky. The unyielding brushwork shades a man who holds up a dripping vessel in front of the sea—a prized discovery amidst the pitfalls of survival.

Ultimately, throughout Castaway, Kim sustains a tone that yearns for rescue. Across these scenes of lonely strife, the artist’s protagonists appeal to be saved from misery. In the same breath, however, Kim uplifts the knowledge that arises from a state of enduring isolation. It is within these moments that one is forced to address the inner workings of the mind and spirit, narrowing in on the inquiries and reasonings that drive us forward. Castaway demystifies the fear of being alone. In this moving exhibition, Kim reveals the latent insight derived from periods of solace.

—Written by Daniella Brito

Castaway

The story of Cast Away (2000), directed by Robert Zemeckis, follows Chuck, a man deserted on an island after an airplane crash. Cast Away is beloved for its dramatic depiction of Chuck’s misfortunes, delirium, and methods of survival on the island. When I rewatched the movie as an emerging artist, I felt a peculiar sense of empathy with Chuck’s isolation and experiences on the island. Before my first solo exhibition with Harper’s in New York, my dream of being a full-time painter felt like an impossible dream. I was truly alone with my paintings in my studio–my own deserted island. I longed for someone to visit my studio and acknowledge that my paintings and I exist.

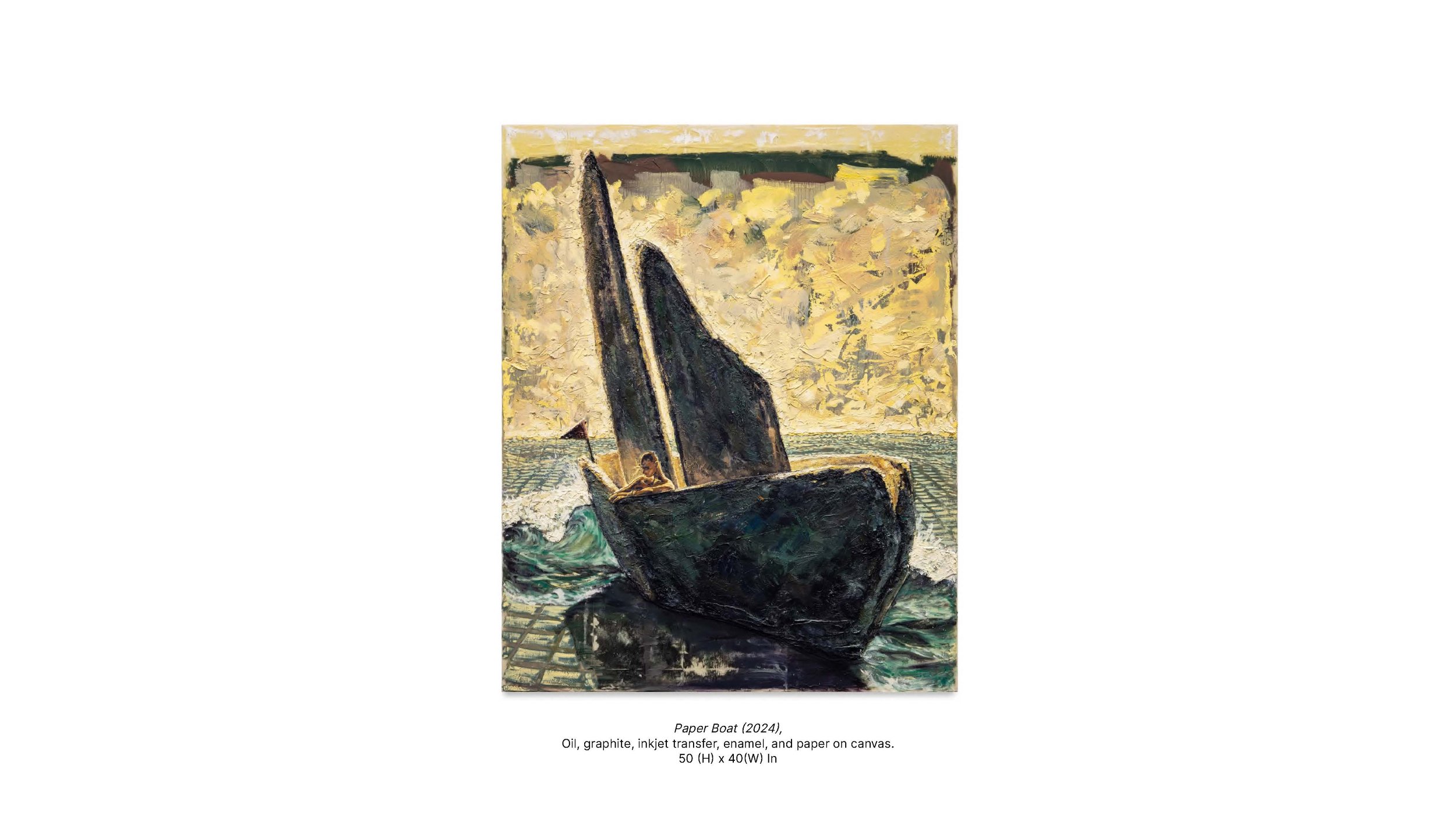

Cast Away became a visual metaphor for my nuanced experience in the studio, one which other working artists might also relate to. In my new body of work, Castaway, I use the film’s environment, props, and themes as a point of departure. Castaway includes 27 new paintings, building a tropical world to interrogate themes of solitude and the artist’s psyche. This new series is a pastiche of motifs from various tales of islands and grand voyages, such as Lord of the Flies, Gulliver’s Travels, and Moby Dick, and images drawn from Christianity.

In Cast Away, Chuck creates Wilson, a personified volleyball, who serves as a friend and confidant on the island. Wilson becomes Chuck’s refuge from loneliness with whom he shares his accomplishments, despair, love, and ambition. Mythical Island (2024) depicts Chuck holding Wilson in a pose reminiscent of Hamlet’s soliloquy, “To be, or not to be.” Wilson's bloody red face, inspired by the Shroud of Turin, drips to the sand below. Like a reliquary object, imbued with the life and body of Christ, Wilson is brought to life by Chuck’s bloodied handprint.

Wilson becomes the physical manifestation of Chuck’s psyche and an extension of the man’s blood and body. Chuck’s exchanges with Wilson blur the boundaries between internal dialogues and external conversations. In the artists’ exile, they create Wilsons, or artworks, physical manifestations of the artists’ history, philosophy, desires, and experiences. Similar to the dualistic nature of Chuck’s conversations with Wilson, the art-making process is both an external exercise and an internal struggle.

Studio Island (2024) references Chuck’s attempted suicide. In Cast Away, this existential scene conveys true despair when all hope seems lost. Chuck survives his suicidal attempt, which leads to a moment of self-recollection and his decision to attempt his escape from the deserted island. The pursuit of passion and dreams exists between hope and despair. All artists desire to be rescued in some way or form. To some, rescue can come in the form of

exhibitions and recognition. To others, breaking one’s plateau or finding one’s true purpose can offer peace. Although we castaways ultimately long for rescue, there is a beautiful nuance that ties us to our deserted islands, or our studio practices. Despite the solitude and hardships intertwined with exile and survival, the studio also provides a space for beauty and purpose. The island is a mythical domain where beauty and anxiety coexist in a perpetual dance.

Purgatory: Re-presenting My Reality

My paintings focus on the ideas of the in-between, the mundane, and the liminal. I call them purgatories. Beyond the religious, there are many purgatories in our contemporary lives when we are neither here nor there but somewhere. Whether it is searching for one’s identity, sitting on a long flight between countries, or walking under endless scaffolds and construction sites in New York, we exist in and around indeterminate states.

I am now fortunate to sustain myself as a painter and make daily connections with my artistic passion. However, I still remember the years when people identified me not as an artist, but as the multiple skins I wore as a restaurant manager, bar director, tutor, and club promoter. For many years, I faced the indeterminacy of striving and longing. Using the theme of purgatory, I can represent the human experience of transience, mundanity, and self-realization in a fantastical way.

In my works, I create imaginary spaces and worlds lit entirely from behind. My viewers are forced to look into the intense light and the silhouetted figures and environments ahead of them. The light and shadow reference Plato’s allegory of the cave, where the cave prisoner’s reality is only composed of shadows, never the real object or light that exists outside of the cave. I extend the imagined space deep into the picture plane and place my viewers in direct view of the monumental objects and light ahead. I hope to provide my audiences with the option to seek the truth that exists beyond the shadows.

Mind Palace (2024) shows a figure standing on turbulent waters, looking ahead into the light. The figure endeavors to stay afloat and look into the light, and the painting’s composition references Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog. Mind Palace is an extension of Friedrich’s romanticism, merging man’s inner psychology with the sublime and breathtaking natural world.

Perhaps reality exists beyond human comprehension and we will never be able to fully grasp its true nature. However, there is beauty to this impossibility. Our inability to comprehend everything in the world allows us to continuously search and wonder about the world around us. Humanity’s fear of the unknown may motivate us to simplify the world into bite-sized truths where we can remain complacent, but this is at the cost of denying potential discoveries. If we allow ourselves to be bewildered by the light of the rising sun or the starry cosmos, we become a part of the greater world, full of its mysteries and potential for exploration.

Between the Strata

Kwon Taehyun

A single painting possesses layers made up of different substances. Merely listing the conventionally used ones—cotton, plaster, glue, oil, paints, graphite, charcoal, and so on—is enough to give us a sense of what a complex mixture of materials a painting consists of. On a small scale, they form material strata of a sort. The reason it can liken them to the Earth’s strata lies in the way they require time to trigger chemical reactions. Sometimes, different materials mix and blend chemically within the painting’s support structure. Other times, independent surfaces form over time to distinguish one layer from the others. A common technique in painting is is to place a combination of different substances on a support structure, allowing layers to form as time passes. Other times, painters will add different substances before the previous layers have dried, creating odd mixtures along their boundaries. They may also adopt a strategy of intertwining this sequence of layers in complex ways by applying substances to just one part of the surface. These issues of material layers represent a key technique of painting as it has developed over the centuries, and painting as a realm has internalized this methodology in its tradition and history. As an artist, Ho Jae Kim adopts fascinating approaches to mediating what occurs between the strata of different materials, as well as the layers of images, symbols, allegories, fiction, and—occasionally—texts that are formed through them.

A glance at even the outermost surface of his work gives a sense of the variety of strata. At times, the media that create textures on the surface clash in disparate ways with the oil painting forms on top of them. A text written in pencil on an inner layer may be covered by a transparent medium, causing it to appear faintly or partially obscure. Throughout, square frame shapes are repeatedly positioned beneath layers of oil. These resemble the marks left by an inkjet transfer, something that the artist also presents in his captions. With this approach, an inkjet printer is used to produce a paper-based version of a computer-generated modeling image; glue is then applied to the bottom of the canvas, and the image-printed surface is affixed to the canvas surface. When the paper is removed, the printer image is transferred to the canvas. This approach can be used to materially transport a digital image onto a canvas. The key point here is not merely about an image being

transferred; it is about a digitally created image being placed on a surface while possessing the same stature as oil paints or various other materials. This reminds us of how the image always exists with its own characteristic materiality. Once the digital image has been transferred, Kim then covers the transferred digital image with gesso and pigments. Here, the digital image becomes the ground and support for an oil painting coarsely rendered by hand and brush. What arises is a juxtaposition of a computer-modeled geometric image with a painterly realm that is constantly deviating from calculations—a shift to a different stratum within the same surface. The computer-based image is covered by different substances, but the grid pattern formed by the successfully affixed sheets of A4 paper leaves rough material marks on the painting’s strata.

Ho Jae Kim has connected this methodology to research into the artist Piero della Francesca. Piero is considered one of the preeminent masters of the era known as the Quattrocento (15th century Italy, which is regarded as the early Renaissance era). What stands out in his work is the geometric appearance of architectural structures and human forms. De Pictura, a theoretical text written by Leon Battista Alberti around the same period, formulates methods for producing images with an emphasis on geometric technique. Notably, one of the central elements in these methods is defined as commensuratio, a term that means something like “commonly used,” “corresponding,” or—in a more etymological sense—“sharing units.” In this context, Piero and his painter contemporaries explored techniques for using mathematical methods to capture the shapes of their subjects, and these methods relate to the visual system that we refer to today as “linear perspective.” The problem is that shapes composed in this way—through vanishing points, straight lines, proportion, grids, and so forth—will sometimes come across as unnatural to us. Part of this has to do with the inability to geometrically represent the world as we perceive it with living and moving bodies, but there is also the issue of what has been referred to as the “uncanny valley.” Ho Jae Kim’s work addresses the dissonance between geometric precision and human perception by intersecting computation-based images with the materiality of painting—merging the digital with the analog.

To be sure, the “uncanny valley” concept has also been used to describe internet memes, which may seem quite removed from the realm of psychoanalytic theory. But it is worth noting the connection that is drawn between the “uncanny” (unheimlich in German) and the odd sensation that arises when a mathematically composed form is translated into hand-rendered painting. The term unheimlich, as its German roots suggest, describes not the emotion we feel when confronted with something utterly new or unfamiliar.

We describe something as unheimlich when something as familiar to us as our own home is perceived as somehow “different.” In this context, it clearly relates to a sense of odd unfamiliarity even as the same thing is repeating and recurring. This explains why the term is so often used in situations where human forms overlap with those of robots, dolls, sculptures, and the like. Here, we might also observe the ways in which the shapes, forms, and colors that appear in Ho Jae Kim’s work recall those of the artist Giorgio de Chirico. In Kim’s paintings, different styles from art history appear repeatedly and without regard for historical sequence; they are more archaeological than historical, like relics from the past breaking through the Earth’s strata to present themselves on the surface of today’s land. Styles, figures, and methodologies from past eras are invoked on Kim’s surfaces, but they do not appear the same as before. They repeat and recur, but they do not carry the same sense as when they are situated in today’s realm of art discourse. The oddness seems to arise from Kim’s methodology of inserting elements from art history in between the strata of his paintings.

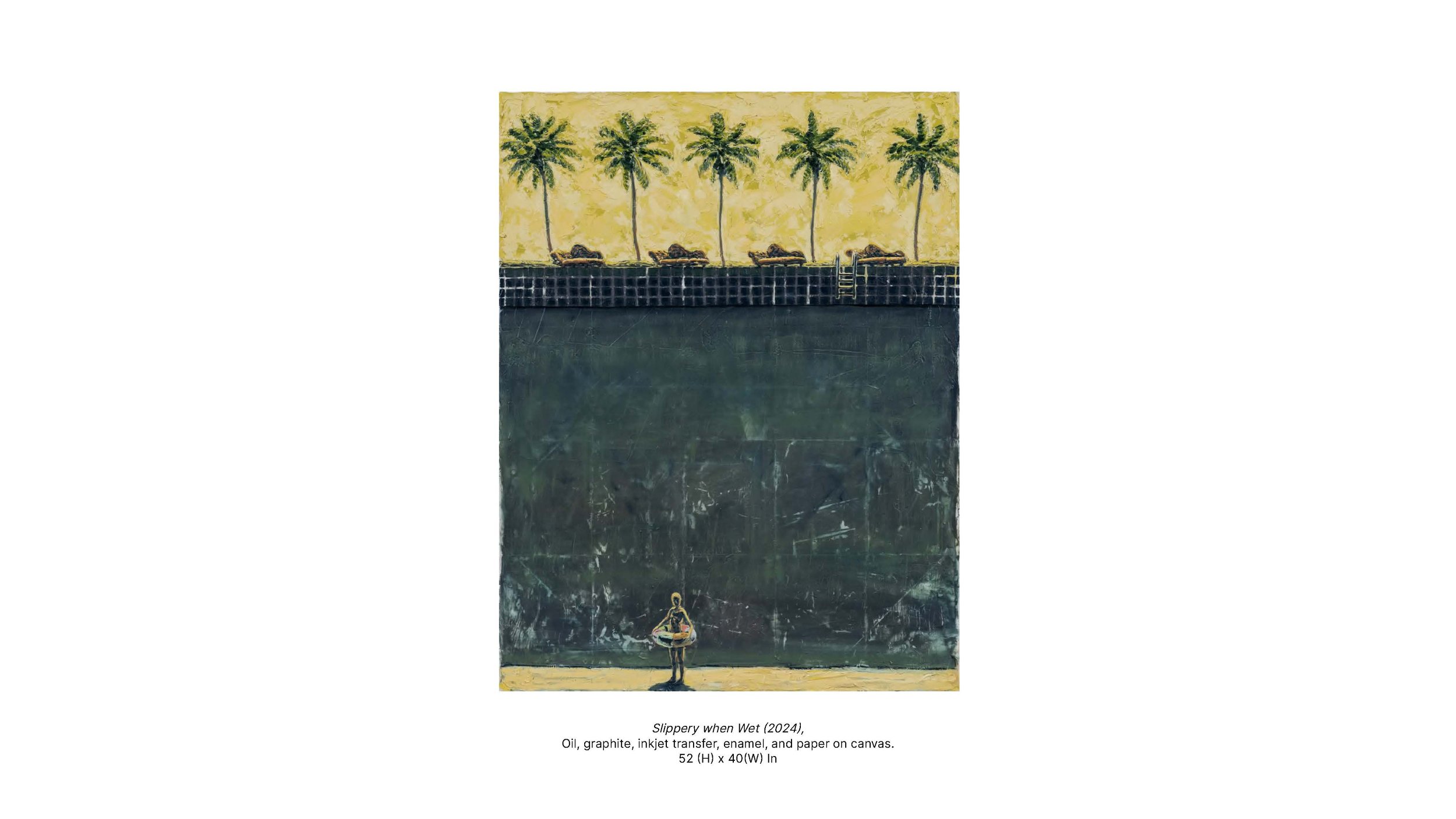

In Ho Jae Kim’s paintings, repetition does not occur solely through borrowings from art history. A unique sense is evoked as figures and compositions are repeated among images from series painted around the same period. The latest series has the underlying theme of a “desert island.” Across various works, we find palm trees appearing as silhouettes against glaring yellow backdrops; people alone on islands; heads that appear chopped off; and “Wilson,” the volleyball friend from the movie CASTAWAY. Within a single canvas, these figures conjuring desert island associations link with various other images outside to evoke connections with “stranding” motifs such as the one in CASTAWAY (the film where Wilson appears) or the stories of Robinson Crusoe and Lemuel Gulliver, while paintings such as Slippery when Wet recall the film Triangle of Sadness, where the characters eventually realize that the uninhabited island they believed themselves to be stranded on is actually just another corner of a tourist resort. The desert island theme in these images does not culminate in a single narrative; rather, its repetition diffuses into multiple allegories. The individual images— typical desert island motifs recalling films or novels, forms from mythology and art history such as torsi and mermen—interrelate in odd ways through their repetition, bleeding off in different directions from the familiar symbols. Kim projects the image of the artist onto the isolated space of the desert island and the person living there;the viewer, in contrast, may discover themselves, or other things that they perceive from

The repetitions and recursions are not confined to the level of shapes. The visually captured shapes on the painting surface are juxtaposed with the volume of the medium underneath, the brushstrokes, and the materiality of the transferred image. This creates a misalignment between the ground and forms. In Slippery when Wet, the top of the image shows rows of chairs and palm trees, significantly repeated with the same shape; the very bottom shows someone standing on a rock with a tube around their body. The broad expanse in the middle presents a space with none of the oil paints that have been used to create the forms above and below. The outermost surface shows a medium with a different texture from the paints. The smaller grid where the middle and upper portions are joined seems to represent the tiles of a swimming pool, but the broader grid beneath exists as materiality itself rather than eliciting some illusory effect. The different materialities in different layers show the completely different orders operating within a single painting. In this series, the grid patterns that are generally visible seem as though they might exist as geometric meshes creating order in the image’s world, but the thick layers of paint and the grid formed by gouging their surface operate under very different approaches. For instance, many paintings show grids sprawling over the surface of an area that is represented as the sea. Here, rather than representing systems that are objectively structured as they undulate with the textures of the painting, they appear instead to show states of fluid transformation. In the aforementioned commensuratio, the grid is used as a way to structure the world along geometric lines. Here, it is put to the exact opposite use.

In his contemplations of the issue of “in-between space,” Kim has often made references to purgatory—a place in between that is neither heaven nor hell. In Christian worldviews, purgatory is seen as a place where people spend time expiating their sins before proceeding to heaven. In Latin, the word purgatorium is a combination of purgo, a verb meaning “to cleanse,” and a suffix indicating a place. The concept was adopted as official doctrine at the Second Council of Lyon in 1274, but it is not something that clearly existed from the early period of Christian history. Around the same time that the concept of purgatory was codified, the Catholic Church began a full-scale practice of selling indulgences:reducing the sin to be expiated from this life for those who gave it money. Nothing had actually changed, but purgatory—a concept created through theological discourse—became an existing space because people believed in it. There is no way for anyone to know if it actually exists; it operates purely through the belief that it really might. Indeed, some people who lived their entire lives as atheists have converted on their deathbeds in the fear that an afterlife like hell or purgatory might exist. The reason that the fiction of purgatory is able to operate in reality is because of our inability to know about the afterlife.

The volleyball Wilson appears as a repeated motif in Kim’s paintings, emerging as an embodied self in the artist’s series as in the film CASTAWAY. In I Am Wilson, it becomes a self-portrait. It is interesting to consider how the “character” came about in the film. The protagonist (played by Tom Hanks) discovers the volleyball in a pile of cargo that has also been washed up on the desert island. He touches it with bloodstained hands and sees the shape of a face on it. A bloody palmprint or other abstract mark becomes an unquestionable face—a being with its own personality. In the film, it is the protagonist’s only companion, a presence for him to project himself upon. So immersed do the viewers become in the narrative that when the volleyball floats away, they feel the same sense of shock that they would if a central character died. The absurd premise of considering a bloodstained volleyball as a “person” is unquestioningly accepted within the structure of fiction. This leads us to consider the potential of objects, images, and fiction.

Layered on the canvas, the substances become very different entities depending on the discourse order or belief system in which they are placed. In many cases, they are representational forms that evoke illusory perceptions—but in different contexts they may also become symbols, allegories, or even narratives. Substances are rearranged into specific orders as they are situated in media theory or formalist discourse. Ultimately, all of it may become mere substance. With his characteristic methods of layering materials that operate in different orders on a single canvas, Ho Jae Kim engages in an exploration of these issues—since it is impossible to know that which is not revealed on the surface, it is conversely possible to investigate some of the traces left behind. What arises is a complex dialectic of surface strata and deeper strata. The forms between strata don't appear as distinct entities but as interactions between conflicting orders—substances that intersect, puncture, and tear through layers, with images surging up from within.

Kwon Taehyun

Taehyun Kwon is a writer and exhibition curator. While active in the field of art, he has always been more interested in things that are not readily recognized as “art.” He has continued focusing his studies on perspectives that perceive the political in terms of sensory matters. A graduate in art history from Korea National University of Arts, he is currently an adjunct professor of convergence arts at Kaywon University of Art & Design.