Ode to Joy

Nicodim Los Angeles | November 4 – December 22, 2023

The lyrics to Ode to Joy, the triumphant final movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, were adapted from Friedrich Schiller’s 1785 poem celebrating strength in unity and the “brotherhood of man.” Beethoven’s version has inspired leaders of political movements as disparate as Mao and Hitler and the European Union—the latter currently employs the piece as the Anthem of Europe. Paradiso, or Paradise, is the third and final act of Dante’s Divine Comedy, which follows the soul’s ascent to heaven following its time in purgatory. With Ode to Joy, Ho Jae Kim’s first solo exhibition in Los Angeles and his first with Nicodim, the artist juxtaposes the two poems in an attempt to find equilibrium between chaos and utopia, neither of which he believes can be sustained without periods of the other.

The exhibition consists of three series. In Utopian Carousel and the five The Hunt of the Monsterworks, Kim imagines his own preamble to Paradiso, in which the viewer is led through various garden scenes that alternate between relaxation and battle. Kim leans heavily on Dante’s notion of purgatory here. His figures that exist without choice are (sometimes literally) stuck on a carousel, condemned to circuit the same stretch of garden for eternity, while those who imbibe in their own free will might either be rewarded in the hunt or damned to expire alone. Some of the characters lived, all of them will die. Kim’s second series features the lyrics to Beethoven’s Ode to Joy etched on Roman ruins. As Beethoven’s Ninth has witnessed time and time again, even the proudest of empires eventually falls, the calamity of its remnants providing platforms and fodder for future chaos and utopias.

Finally, Kim’s epic, two-and-a-half meter The Garden depicts a sort of equilibrium between the anarchy of the garden and a version of state-implemented utopia on top of it. Though the edges are crumbling, a griffin, a symbol of stately power, sits proudly at its center, acutely unaware of its own fallibility.

Kim’s process itself is an allegory for the narratives contained within his work. To create each canvas, he starts with an image transfer and builds it up with layers upon layers of enamel before carving it down and recreating an approximation of the original image on top. It is a constant push-and-pull between chaos and order. Like the images from which Kim begins his paintings, history is often flattened into ideological caricatures and recycled to service contemporary power structures. With Ode to Joy, Kim labors to demonstrate the poetry, nuance, and depth that initially illuminated them. This work is alive.

—Written by Ben Lee Ritchie Handler

For those who may not be fully familiar with your work, I think it would be important to re-contextualizing this series within your practice, but also as it relates to your previous show at Harper's that was produced shortly prior. Could you give us an overarching view of where this specific series lives within the broader context of your work?

When it came to preparing this following piece, I know you had a specific narrative in mind around paradise, myth making, idols/icons. Can you walk us through the broader ideas behind this show?

HJK: When readers transition out from the Inferno and to Purgatory, Dante turns right to see the light from the east on Easter Sunday, a day of resurrection. With a new orientation, the Purgatory of Dante, in contrast to the Inferno, becomes a domain that can nurture the hopes for the future as a place of freedom where lost souls can choose to repent, or in my less religious phrase, where lost individuals can find redemption. As one of the poem’s main themes, the idea of choice is crucial because such is the factor that can allow for a future and moral life.

The centerpiece of this exhibition, its namesake painting, depicts a carousel with 31 horses signifying the days of the month. For each of these “days,” I built a unique narrative in honor of liminal spaces, the mundane and the quotidian. The horses in the painting, Carousel (2023) are painted to face left in the direction of the spiraling Inferno. However when the audience chooses to imagine the mechanism rotating, the horses will eventually turn right as the horses reach the other side of the pillar.

Similarly, as the recurring symbols and motifs such as halos, arches, circles, and magnificent light become juxtaposed with the mundanity of the subject matter, prisoners of my narratives are given redemption. The magnificent light and religious symbols transform the quiet non-moments into moments of divinity. Such is to say, no matter the situation or occupation in life, each individual is the protagonist of their own story. Every story is divine. If one can choose to see the inherent beauty that's embedded in life itself, a life, no matter how insignificant, is worth living.

HJK: Following the recent solo exhibition at Harper’s, Carousel, which thematically embraced the Inferno and Purgatory from Dante’s Divine Comedy, the solo exhibition at Nicodim, Ode to Joy, continues the journey and arrives at the final realm, Paradise. Ode to Joy utilizes the idea of gardens as a thematic tool to help conceptualize my contemplations toward the idea of peace. In classical literature, the image of the garden was used as a literary device that forewarned danger because it is a seemingly peaceful place where protagonists laid down their arms to rest. Here, even the most formidable hero would become vulnerable, becoming an epic’s setting for significant conflicts. This literary device, common in Greek mythologies, is at the foundation of Western literature’s DNA. The symbol is reused in the Garden of Eden in the Christian faith, Alice in Wonderland, and more.

What is paradise, or interchangeably, what is peace? Are we truly happy in the false sense of utopias or are we more alive in chaos where the ground is fertile with choices and possibilities?

Let’s get into the specific aspects of each scene and their meaning as part of the overarching story?

HJK: If one can look deeper beyond art's aesthetics, one can begin to acknowledge its functionality. Although art is inherently a medium for storytelling cultural, historical, and personal narratives, it may not always be readily available for audiences to engage profoundly. Not only do I desire to create artifacts materialized from stories and ideas I’ve collected in my lifetime, but I also wish to make those accessible to as many people as possible. People are built on stories as they inspire and motivate. Stories can be life-altering, and society is built on a foundation of them.

Ode to Joy is a body of work built of three miniature series: The Garden, The Hunt of the Monster, and Poems. The Garden consists of two paintings, The Garden (2023) and Utopian Carousel (2023). The two paintings describe the setting of a garden, a metaphor of the contemporary society that we live in today – seemingly peaceful yet dystopian. The giant 14ft painting depicts a crumbling structure while the other portrays a circle of people stuck in a circular ritual.

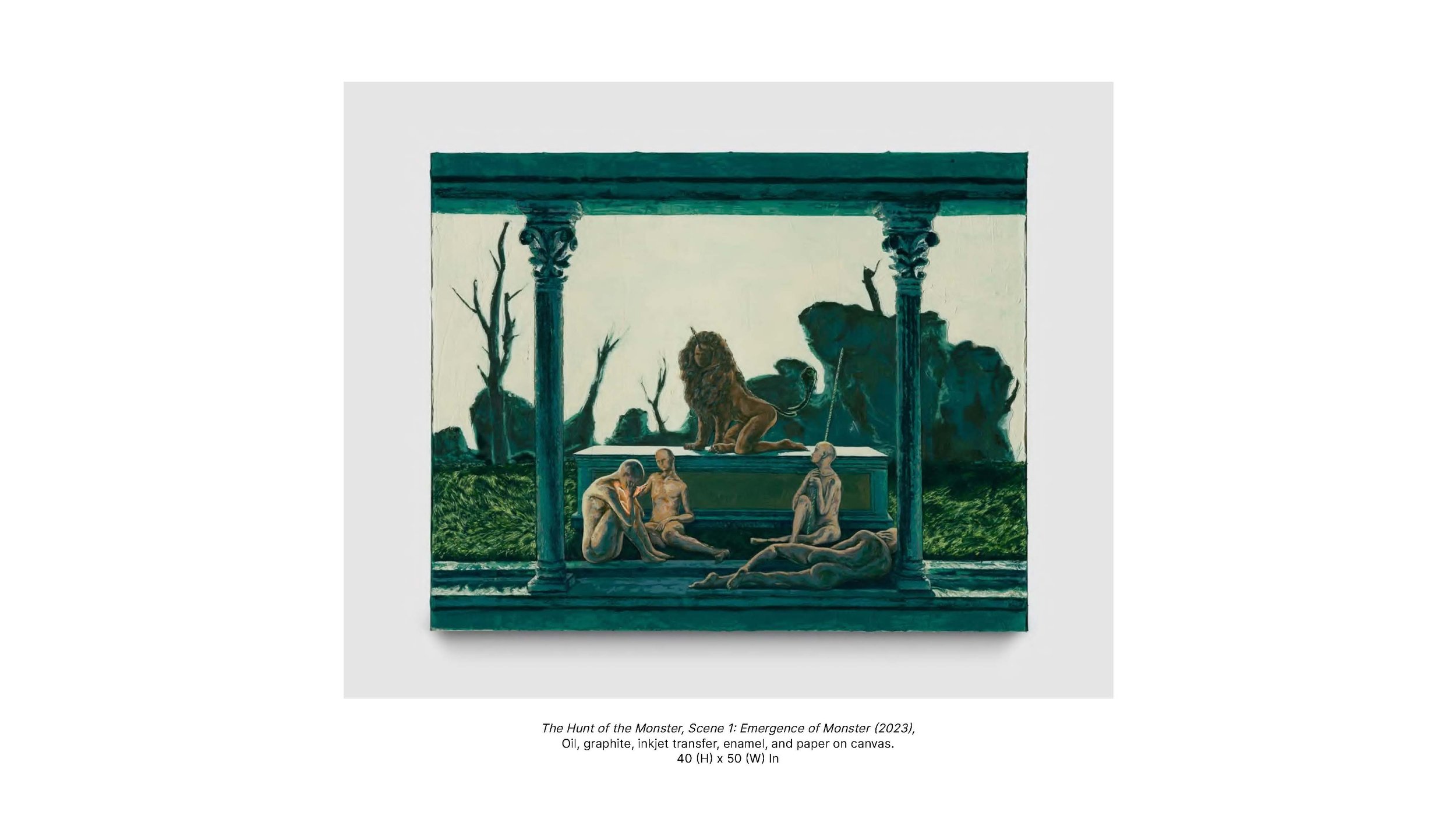

The Hunt of the Monster is a short story referencing the historical narrative of Christ – birth, persecution, and embrace. Five paintings in this series depict each of five frescos painted in The Garden, and therefore the centerpiece becomes a re-presentation of the narrative depicted in The Hunt of the Monster.

Lastly, the six poem pieces are paintings of each verse of the lyrics to Ode to Joy carved into stone. Independently, the stone pieces describe the religious and ideological sentiments of the realm, and together, they form the crumbling architecture depicted in The Garden. This towering structure casts a shadow over people.

[Narrative] Monster appears in a sleepy garden where no trees are alive.

[Concept] A monster is a more appropriate representation of us than a singular being, deity, or creature. A monster, whether a manticore or Frankenstein's Monster, is a queer assemblage of ideas, concepts, and origins. No individual can be simplified into a single idea or origin. One’s history, culture, and genealogy, especially in today’s globalized economy, are a combination of multiple origins. Compositional reference: The Resurrection (1465), Piero della Francesca

[Narrative] The garden finds peace and harmony with the presence of the Monster. Animals, creatures, and Monster are pleasantly resting by the water. However, there is a dark figure lurking in the background with its arms crossed. Flat trees are abundant in the garden.

[Concept] Compositional reference: The Unicorn is Found from The Hunt of the Unicorn, Tapestry by Meister der Apokalypsenrose der Sainte Chapelle

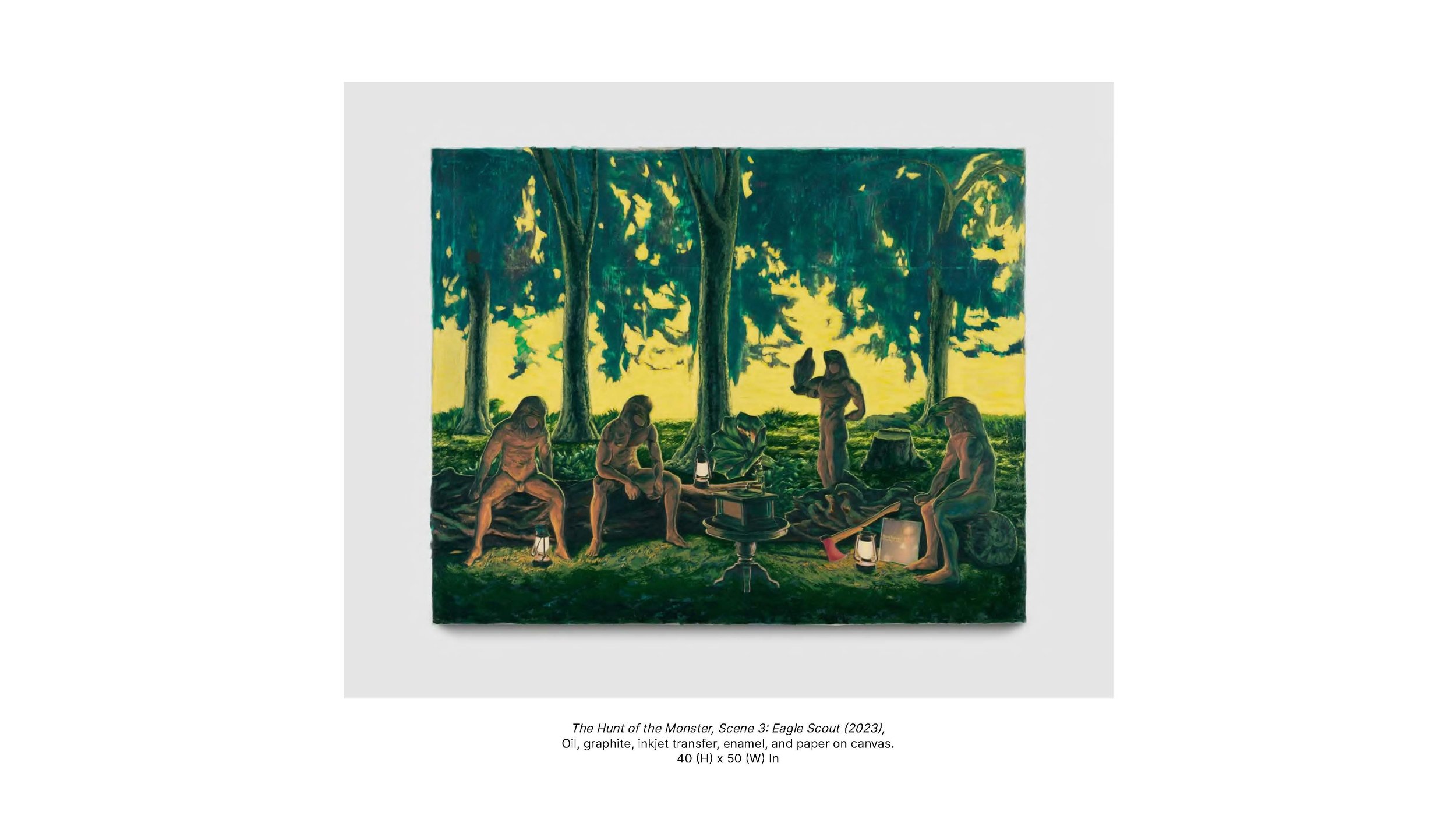

[Narrative] Eagle People are scheming. They are discontent with the presence and the influence of the Monster. A different type of tree, a kind that is commonly associated with Yosemite national park, is in the background. An axe is seen in the composition and the chopping of trees is introduced to the narrative.

[Concept] Beethoven’s 9th Symphony, 4th Movement (Ode to Joy) is an ideological masterpiece. As music of universal adaptability, it was used by polarizing political movements throughout history: Ode to Joy was used in Nazi Germany to celebrate significant public events; Beethoven was lionized in the Soviet Union, andOde to Joy was used as the song for the communists; when most western ideas and culture were censored in China during the great cultural revolution, Ode to Joy was one of the few that was not; on the extreme right, Ode to Joy became Southern Rhodesia (before it became Zimbabwe) when it declared independence; on the extreme left, President Gonzalo of Peru declared that Ode to Joy was one of his favorite music when asked by a reporter; today, Ode to Joy is the unofficial anthem of the European Union.

As masculine music of grandiosity and divinity, Beethoven’s Ode to Joy is the background music of universal fraternity – a musical brotherhood. Listening to Ode to Joy is like imagining leaders of politically polarizing ideologies (Hitler, Stalin, Mao, Bush, etc) all merrily listening to their favorite music together. Similarly, an eagle is a bird that was used as a symbol of power throughout history: eagle was an animal that symbolized Zeus in Greek mythology; eagles were used as emblems of various monarchs and states, including those of Germany, Romania, and Poland; Nazi Germany used eagles alongside the Swastika; eagles are found in the Great Seal of the United States as seen on the dollar bill.

[Narrative] Eagle Person is riding a deer creature while commandeering hunting dogs. Flat trees, associated with Monster, are chopped. People, unaware of the violence, are enjoying the sunset.

[Concept] Compositional reference: The first episode of the Tale of Nastagio degli Onesti (1482/83), Botticelli

[Narrative] Eagle People are executing Monster. All flat trees are chopped and from the trunks, Yosemite trees are growing.

[Concept] Referencial to the persecution of Christ. Image reference to St. Sebastian, an early Christian Saint and Martyr. In medieval times, Saint Sebastian was regarded as a saint with an extraordinary ability to intercede to protect from plagues.

HJK: The third scene of The Hunt of the Monster depicts a brotherhood of eagle-like creatures gathered around a phonograph playing the final movement of Beethoven’s 9th symphony, Ode to Joy.

Ode to Joy, a masculine music that was conceptually composed with the idea of revolution (born from Beethoven’s idealism of the French Revolution), and the symbol of the eagle were both used throughout history to embody political and religious institutions of power. The symbols, ranging from democratic to totalitarian and paganism to modern, are up close and polarizing to each other. However, when indexed with the common denominator of ‘the masculine pursuit of power,’ ideologies look similar, regardless of fundamental differences.

With the introduction of Eagle People in the third scene, an axe is present in the picture, hinting at the idea of tree-chopping, and as the hunt for the Monster begins, the scenes depict the tree associated with the Monster (flat trees) being chopped down. In the final scene, as the Monster is executed, all the flat trees are cut, and from the trunks, blossom trees are associated with Eagle People (Yosemite-esque trees).

Symbols do not disappear. Instead, symbols stay, and meanings adapt. Much of today’s symbolisms commonly used in popular culture date back to Christianity and then even further back to paganism.

Apart from the two masculine figures, Monster and Eagle People, there is a group of skinny bald figures in the garden, representing the masses. The masses are always depicted sleeping or looking away, unaware of the violence in the garden. The masses are unaware of the changing history unfolding so close to their proximity.

What was the meaning beyond recomposing these various pieces as part of this giant broader composition?

HJK: The Garden (2023), the centerpiece of Ode to Joy, is a painting of a series of frescoes surviving on a ruins wall. Depicted frescos are cartoons (flattened images) of each scene from The Hunt of the Monster, Scenes 1 - 5. By the exactitude of similarities in the number of scenes and compositions, the frescos become a re-presentation of the story told by The Hunt of The Monster paintings. Scenes 1 - 4 are one-to-one regarding the figures and their actions. However, the last scene is different. Where the last scene of The Hunt of the Monster depicts the Eagle People killing the Monster, the last scene of the frescos depicts the Eagle People embracing their adversary.

The established narrative of this series is an allegory to Christ's historical (not metaphysical) narrative. Christ, who was persecuted and publicly executed, was initially seen as a cult leader by the Romans and then eventually embraced as the symbol of the Roman Empire for political reasons.

Those in power have the ability to alter narratives. Institutions have the capability to rearrange truths and individuals’ histories and ethos. Such is not only a phenomenon of the past but a discrepancy that is even more apparent in today’s current events. Consumerism, propaganda, social media, pop culture, and politics thrive when they control narratives. Truths are invisibly or visibly changed to embrace the support of the masses, and therefore we are constantly lost in the discrepancy of narratives caught between those in power. Through endless layers of subjectivities, people lose direction, not knowing how to describe reality and the origins of history.

The Garden (2023) and The Hunt of the Monster, Scenes 1 - 5, portray two versions of the same story. The exhibition is composed to superimpose the discrepancy of the narrative and situate the viewers in between two versions of the truth.

You chose to add a series of conceptual works or ‘poems’ in the show, as to push further the relationship to the overarching theme and title of the show. Can you give us more insight on this series?

HJK: The poem, ‘Ode to Joy’ was written by German poet Friedrich Schiller in 1785 and then revised in 1808, where Beethoven used it in his final fourth movement of his Ninth Symphony with a slight addition. Beethoven’s famous fourth movement of the 9th Symphony was intended to be revolutionary as Beethoven was inspired by the idea of heroism and the French Revolution.

The six poem pieces in the series are paintings of each verse of the lyrics to Ode to Joy carved into stone. After building a rock-like surface, a sculpting tool was used to carve into the painting literally. Ideas and truths become building blocks of institutions—ideas, once novel and man-made, over time become towering structures that cast shadows on mankind. When ideas become ideological, people abide by them as if they are laws of nature, forgetting their ontological immaterialities.

HJK: The process and concept of my paintings emphasize the importance of depth and layered histories. When the painting is finished, not all of the parts of the process are visible on the surface. However, just because something is invisible does not mean something does not exist. A painting is like a person. Each person is a container of a lifetime’s stories and experiences. When we encounter each other, we can only see the physical shell presented on the surface, but we also can be conscious of each person's history. Similarly, the many steps of my paintings are the painting’s genealogy and history. Although the steps are not readily visible on the surface, if one step of the process were to be removed, the paintings would take on a very different look.

Conceptually, the paintings have layers of images and symbols so that the series can be deconstructed and reconstructed. For example, a viewer can notice that the individual stone blocks could stack on top of each other to become the large wall depicted in the centerpiece or that the large wall of the ruin could be broken down into small individual Poem pieces. If each poem block is an engraved object of ideology, then the centerpiece is an erect, ideological architecture that towers over people. The fresco images on the centerpiece can also be seen individually in the five Scene paintings. The audiences have the ability to look at the narrative of the series individually and as a whole.

We lack the ability to find depth in images today. The alarmingly disconnected and dystopian society today is a symptom of the illness that burgeoned from the speed and overproduction of information and images. Most of us are unaware of the origins of the terminologies and symbols that we use. We are too often lost in the vast ocean of polarizing opinions without the ability to find objectivity and credible sources of information. We consume and republish too quickly and we cannot grant ourselves enough time to uncover the depth and quality that exist in all things. The two series I made in 2023 were my attempts to create an idea where my audiences are given the chance to slow down to deconstruct and then reconstruct the images and ideas that I provide.